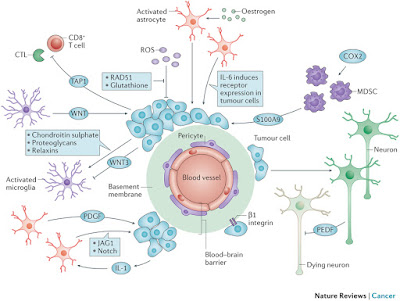

Tumour metastasis, the movement of tumour cells from a primary site to progressively colonize distant organs, is a major contributor to the deaths of cancer patients. Therapeutic goals are the prevention of an initial metastasis in high-risk patients, shrinkage of established lesions and prevention of additional metastases in patients with limited disease. Instead of being autonomous, tumour cells engage in bidirectional interactions with metastatic microenvironments to alter antitumour immunity, the extracellular milieu, genomic stability, survival signalling, chemotherapeutic resistance and proliferative cycles. Can targeting of these interactions significantly improve patient outcomes? In this Review preclinical research, combination therapies and clinical trial designs are re-examined.

Metastases, or the consequences of their treatment, are the greatest contributors to deaths from cancer. Clinical metastatic disease results from several selective forces. Pathways that fuel initial tumorigenesis, described as the 'trunk' of a cancer evolutionary tree, can also endow tumour cells with metastatic properties and de novo drug resistance. Two types of 'limb' pathway emerge from the tree trunk: events that induce acquired resistance to therapy and pathways that induce or accelerate metastasis to distant organs1. Cancer therapy has largely concentrated on druggable targets in the trunk tumorigenesis pathways, such as receptor tyrosine kinases, and uses sequential and combination therapies to minimize drug resistance.

Source: NatureReviewsCancer

No comments:

Post a Comment